This winter I took a three-week trip to Ethiopia. Man, am I still processing my experience. I went to the north to the countryside near Lalibela; spent time in the capital, Addis Ababa; and in the South Omo Valley, along the borders of Kenya and South Sudan and home to a number of remarkable tribal people.

A picture, just to whet your appetite, of Daasanach girls dancing. If you read on, you’ll discover how the love of fabric—one scarf in particular—has woven together three women on opposite sides of the globe.

OK, let’s be frank: Addis is a tough, merciless place. Thankfully, I made friends who made my visit memorable: Mihiret (aka Mercy the Miraculous), Lydia, Sophia and Monte. They, and the fair-trade weaving center called Sabahar, became my personal sanctuary.

Founded by a Canadian woman, Sabahar is an incredible resource that draws talent from Ethiopia’s tribal weavers—specifically, the Dorze people—to make beautiful, sustainably woven goods in designs that certainly grabbed my eye.

Below is one Dorze settlement I visited in the south. Even the houses appear to be woven.

In Sabahar’s spinning room, a sociable group of women were twisting cotton and silk into hearty threads. The silk is interesting; the worms feed on a local leaf, not the usual mulberry, which don’t thrive in Ethiopia’s climate. The silk fibers are often dyed using natural dyestuffs because they will be more likely to be hand washed. The cottons and linens use chemical dyes, but they are reclaimed somehow before entering the wastewater. Water is precious here.

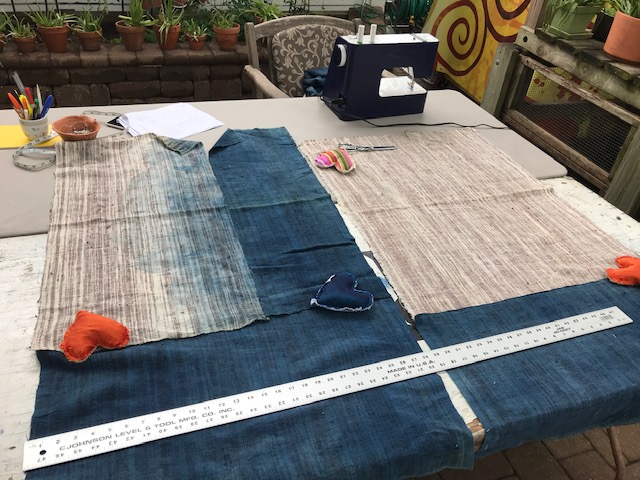

The men occupy the weaving room. Clean and bright, it had multiple looms going at once. The weavers were working on an order for a Brooklyn-based design client: Bolé Road Textiles.

I noticed indigo dangling overhead. But the truth is, Chinese import textiles have triumphed everywhere in Ethiopia. Which is depressing. I can’t tell you how many mounds of disposable jelly shoes I saw.

My last day in Addis, Lydia (top), Sophia and I made the pilgrimage to Sabahar. Irresistible!

So here’s the story of The Scarf. When my guide-goddess Mihiret took me to visit the Karo tribe, Bonnie, in yellow beads, wanted the big long ikat scarf I was wearing. Big time. I bought it near Lalibela, where all the local dudes wrapped themselves in similar versions. I wore it for three weeks straight to keep the sun off my face and so I could mop my sweat. On it was “Star of Africa,” but I’m sure it was made in India or China. I didn’t want to engage in a transaction with her, so I shook my head. She didn’t seem to mind.

Later, back in my hotel room, I looked at the scarf and thought, “Why on earth do I need another damned scarf when Bonnie has none?” So I asked Mihiret to give it to her when she saw her next. I cleaned it first, of course, and wrapped hotel soaps in it.

Two weeks later, Mihiret sent me these pictures. Seeing them honestly made my year. She looks gorgeous and it’s where it belongs, in Africa.